Imagine a world without laws—no traffic rules, no property rights, no consequences for theft or violence. Chaos would reign. Now, consider that the very idea of codified law—a set of written rules binding everyone in a society—originated over 3,800 years ago in a dusty, river-fed region called Mesopotamia. This ancient civilisation, often overshadowed by Egypt or Greece in popular imagination, laid the groundwork for modern legal systems. From the concept of ‘an eye for an eye’ to the presumption of innocence, Mesopotamian innovations in law continue to echo in courtrooms today. This article explores how these early legal pioneers shaped justice, structured societies, and left a legacy that still influences how we think about fairness and order.

Mesopotamia—Greek for ‘land between the rivers’—encompassed the fertile plains between the Tigris and Euphrates in what is now Iraq, Syria, and parts of Turkey and Iran. From around 3500 BCE, this region saw the rise of city-states like Ur, Babylon, and Nineveh, each with complex bureaucracies and social hierarchies. Writing, invented here circa 3200 BCE via cuneiform script, was pivotal. It allowed laws, once transmitted orally, to be etched into clay or stone, creating permanent records accessible across generations. The Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians each contributed to legal evolution, but the most famous milestone came circa 1754 BCE with the Babylonian king Hammurabi’s law code. However, Hammurabi’s work built on earlier efforts, such as the Code of Ur-Nammu (circa 2100 BCE), the oldest known legal text, which established fines instead of corporal punishment for offences.

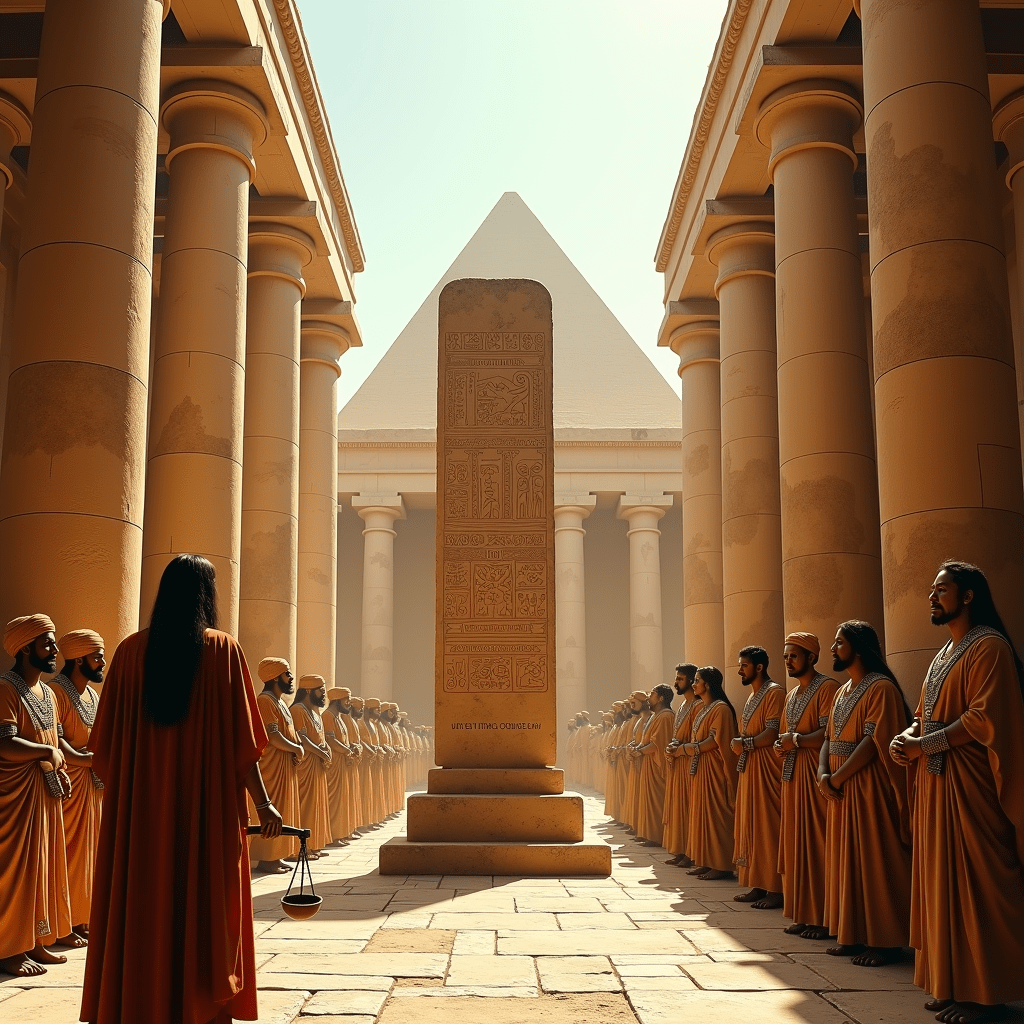

The shift from oral custom to written law was revolutionary. Prior to codification, disputes were settled by local elders or rulers, with outcomes varying by memory or bias. Written codes standardised justice, making it predictable and transparent. For instance, the Code of Ur-Nammu, attributed to the Sumerian king Ur-Nammu, listed specific penalties for harms like bodily injury: “If a man knocks out the tooth of another man, he shall pay two shekels of silver” [1]. This precision aimed to curb vendettas by replacing tribal vengeance with state-administered compensation. Hammurabi’s Code, inscribed on a 2.25-metre basalt stele, expanded this approach with 282 laws covering everything from trade disputes to marital rights. Its famous principle of lex talionis (“If a man destroys the eye of another man, they shall destroy his eye”) [2] emphasised proportionality, though it applied only to social equals—a reminder that Mesopotamian law was deeply stratified.

Legal systems mirrored Mesopotamia’s rigid social hierarchies. Laws distinguished between three classes: free elites (awilu), commoners (mushkenu), and enslaved people (wardu). Penalties often depended on the victim’s status. For example, harming an awilu might cost the perpetrator a limb, while the same offence against a wardu required only financial compensation [3]. Women, though subordinate to men, had legal rights unheard of in many ancient societies. Dowry agreements protected wives in divorces, and widows could inherit property. The archives of the city of Nippur reveal cases where women sued male relatives for withholding inheritances—and won [4]. Such nuances challenge the stereotype of ancient women as mere property.

Mesopotamian courts were surprisingly sophisticated. Judges, often priests or officials, heard evidence from witnesses and examined contracts. The accused could present defences, and verdicts were recorded in detail. A tablet from Larsa circa 1800 BCE documents a trial over a disputed sale of land, complete with witness testimonies and a ruling in favour of the buyer [5]. Perjury was severely punished; Hammurabi’s Code warned, “If a man bears false witness in a case, and does not establish the statement he has made, if that case is a case involving life, that man shall be put to death” [2]. This emphasis on truthful testimony underpins modern legal practices like oath-swearing.

The legacy of Mesopotamian law is immense. The Hebrews likely drew from lex talionis when framing Mosaic Law (“an eye for an eye” appears in Exodus 21:24). Greek and Roman legal systems, though more abstract in philosophy, adopted Mesopotamian concepts of written statutes and judicial procedure. Even today, the idea that laws should be publicly accessible—as Hammurabi’s stele was displayed in Babylon—resonates in democratic ideals of transparency. As legal historian Raymond Westbrook noted, Mesopotamian law “represents the first attempt to create a comprehensive system of justice applicable to all members of society” [6], albeit within the period’s social constraints.

Scholars debate how widely these codes were enforced. Some argue they were aspirational, projecting royal authority rather than daily practice [7]. Others point to court records showing laws being applied, albeit inconsistently [8]. Either way, their symbolic power was profound: by claiming divine mandate (Hammurabi’s stele depicts him receiving laws from the sun god Shamash), rulers linked justice to cosmic order, legitimising their rule. This intertwining of law, religion, and politics persists in many modern legal systems.

In conclusion, Mesopotamia’s legal contributions—written codes, judicial procedures, and the notion that law should reflect societal values—form bedrock principles of global jurisprudence. While their harsh penalties and social inequalities jar modern sensibilities, their emphasis on accountability, evidence, and accessibility remains relevant. As we grapple with issues like AI governance or transnational justice, it’s worth asking: how might future societies judge our legal innovations? Will our codes seem as revolutionary in 4,000 years as Hammurabi’s does today?

References and Further Reading

- Martha Roth, Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor (2nd ed., 1997).

- Code of Hammurabi, trans. by L.W. King (1915).

- Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East (3rd ed., 2016).

- Samuel Noah Kramer, History Begins at Sumer (1956).

- Eleanor Robson, “Mesopotamian Law,” in A Companion to the Ancient Near East (2005).

- Raymond Westbrook, A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law (2003).

- Jean Bottéro, Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods (1992).

- Sophie Démare-Lafont, “Judicial Decision-Making in the Bronze Age,” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History (2014).

Further Reading

- The Ancient Near East: Historical Sources in Translation by Mark Chavalas.

- Women’s Roles in Ancient Civilisations edited by Bella Vivante.

- Online resource: The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL).

Leave a comment