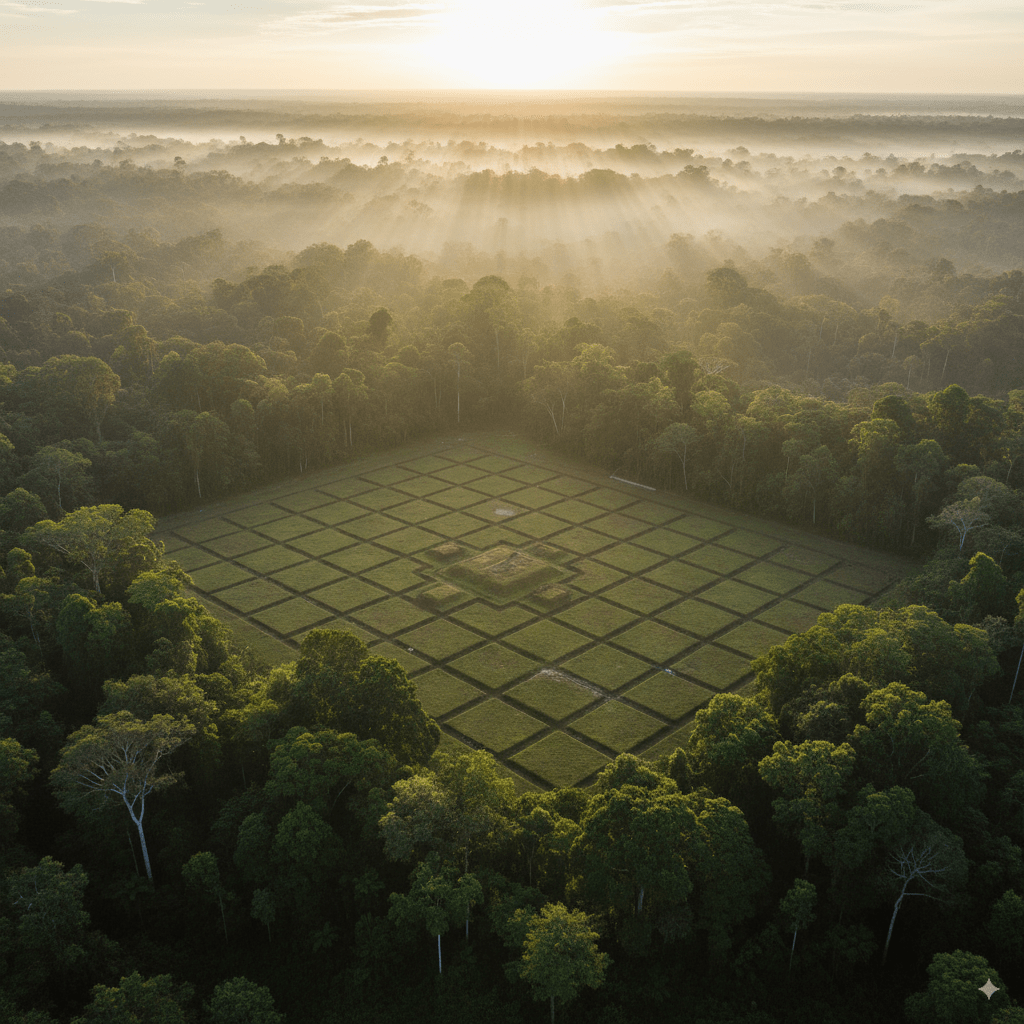

It often begins with a faint, unnatural line on a satellite image. A geometric ghost lurking beneath the dense canopy of the Amazon, visible only from orbit. Guided by this digital whisper, a team on the ground hacks through the suffocating humidity and tangled vegetation. And then, they find it. Not a temple or a pyramid, but something far more profound: the vast, grid-like earthworks of a city, a complex society, that thrived for centuries before being utterly swallowed by the forest. These discoveries do more than just add a new chapter to our history; they force us to question the very durability of our story, revealing that entire civilisations can vanish, leaving behind not even a name.

This image of sudden, dramatic rediscovery feeds a popular conception of civilisational collapse—a Hollywood montage of fire, invasion, and ruin. The reality, however, is often quieter, more complex, and perhaps more unnerving. Collapse is less a singular event and more a process: a rapid, often irreversible simplification of a complex society. Grand cities are abandoned, trade routes wither, and populations decline. But perhaps the most haunting loss is that of knowledge. Imagine a world that has forgotten how to build an aqueduct, how to read its own ancestral script, or how to chart the heavens. This is not a hypothetical scenario. In a shipwreck off the coast of a Greek island in 1901, divers recovered a lump of corroded bronze. For decades, its purpose was a mystery. When finally analysed with modern imaging, it was revealed to be the Antikythera mechanism—a breathtakingly sophisticated astronomical computer of interlocking gears, capable of predicting eclipses and tracking the movements of the cosmos. Nothing approaching its complexity would be seen again in Europe for nearly 1,500 years. This single, tangible object is a stark testament to a profound societal amnesia. It proves that a society doesn’t just lose its buildings, but its very intellect, its memory of how to achieve greatness. The true nature of collapse, then, is the loss of everything.

To understand how this loss can happen, we can look to the well-documented falls of history’s giants. These cases provide a set of ‘usual suspects’—the recurring pressures that can cause a complex society to unravel. The fates of the Western Roman Empire and the Classic Maya civilisation in the Yucatán serve as two distinct and powerful cautionary tales.

Rome was not conquered in a day, nor did it fall in one. Its collapse was a slow, grinding process of systemic fragility. The Empire had become a victim of its own success—too vast, too complex, and too rigid to adapt to the mounting internal and external pressures. The cost of maintaining its sprawling borders, garrisoned by an increasingly non-Roman military, became unsustainable. Political instability became endemic, with emperors rising and falling with numbing regularity, leading to chronic corruption and civil wars that drained the treasury and eroded public trust. The intricate network of trade that was the lifeblood of the Empire began to fray, leading to economic decline and hyperinflation. When waves of external tribes, themselves displaced by larger geopolitical shifts, began to press on its borders, they were pushing against a structure that was already hollowed out from within. Rome’s fall wasn’t a simple case of barbarian invasion; it was the terminal stage of a long illness, a cautionary tale of how internal decay and a failure to adapt can bring even the mightiest superpower to its knees.

The story of the Classic Maya collapse offers a different, though equally stark, lesson. For centuries, their civilisation flourished in the challenging environment of the Mesoamerican lowlands. They built spectacular cities, developed a sophisticated writing system, and created a calendar of astonishing accuracy. Their society was supported by intensive agriculture, ingeniously adapted to the seasonal rains. But this very success contained the seeds of its downfall. As populations grew, more and more land was cleared for farming, leading to widespread deforestation and soil erosion. When the climate patterns shifted in the 8th and 9th centuries, bringing a series of prolonged and severe droughts, the finely tuned system broke. The wells and reservoirs dried up, crop yields failed, and the cities, once the vibrant centres of culture and power, could no longer sustain their people. The collapse was not sudden but staggered, a desperate decline over a century as city after city was abandoned to be reclaimed by the jungle. The Maya provide a tragic environmental parable, demonstrating with chilling clarity that even the most intelligent and resourceful societies are ultimately tethered to the stability of their climate and the health of their ecosystem.

These well-studied examples, however, rely on written records and enduring stone monuments. They are the collapses we know about. But what if they are simply the most recent, the ones that occurred in an age where the evidence was more likely to survive? This brings us to the ghosts in the machine—the tantalising, mounting evidence for advanced, prehistoric civilisations that rose, fell, and were almost entirely erased from memory.

The most profound of these is Göbekli Tepe. Unearthed in southeastern Turkey, this site has overturned our entire understanding of the Neolithic Revolution. It is a vast and complex temple, built not by farmers, but by hunter-gatherers some 11,500 years ago—a staggering 6,000 years before Stonehenge. Its intricately carved T-shaped pillars, some weighing over 15 tonnes, are arranged in great circles. The level of social organisation, architectural planning, and artistic skill required to create it is utterly at odds with our previous image of the Stone Age. It suggests a complex, settled society existed long before the advent of agriculture, pottery, or writing. Yet, after centuries of use, an even deeper mystery unfolds. Its creators undertook a task perhaps as monumental as its construction: they deliberately and painstakingly buried the entire complex under thousands of tonnes of earth, backfilling the sacred enclosures and creating the artificial hill that preserved it for millennia.

Why? The question is as profound as the site itself. Was it a ritual act, a way of decommissioning a holy place that had served its purpose? Was it an attempt to hide it from an impending threat, or to protect it from a society that was collapsing around them? Or could it be something more? Could it have been an act of incredible, far-sighted preservation? A message in a bottle, not of words, but of stone, left in the hope that a future civilisation might one day unearth it and understand. This last possibility is staggering. It suggests a consciousness of deep time, an awareness of the cyclical nature of existence that is both humbling and deeply moving. It transforms these ancient people from victims of collapse into the knowing curators of their own legacy. Alongside the submerged prehistoric landscapes of Doggerland in the North Sea and the ghostly urban grids beneath the Amazon, Göbekli Tepe stands as a silent monument to the fact that our known history is merely the visible shoreline of a much deeper, submerged past.

What, then, are we to make of these echoes? It is tempting to draw direct parallels, to scan our own global civilisation for the fractures of Rome or the droughts of the Maya and to sound an alarm. But perhaps the truest lesson these forgotten worlds offer is not one of fear, but of philosophical perspective. By acknowledging the fragility of our own complex systems—our intricate global supply chains, our delicate climate balance, our instantaneous communication networks—we are not succumbing to fatalism, but engaging in a necessary act of humility.

The stories of collapse, both known and unknown, suggest that the rise and fall of civilisations may not be an aberration, but a natural rhythm in the long human story. Complexity is achieved, but it comes at the cost of fragility. Simplification, while often traumatic, allows for reorganisation and renewal. By looking back at the ghosts of worlds that have vanished, we can better understand our own place in this grand, unfolding pattern. Perhaps we are not the final, triumphant chapter of the human story, but merely the latest, flickering brightly before inevitably taking our place in the deep, silent archives of time.

Leave a comment