Imagine trying to run a city, manage trade routes spanning hundreds of miles, or even just remember who owes you what, all without writing a single word down. Seems impossible, doesn’t it? Yet, for millennia, human societies functioned entirely through spoken word and memory. That all changed in the sun-baked plains of ancient Mesopotamia, the land nestled between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is modern-day Iraq. It was here, over 5,000 years ago, that one of humanity’s most profound inventions emerged: writing. This wasn’t just about scratching symbols onto clay; it was a revolution that reshaped societies, enabled empires, preserved knowledge, and ultimately paved the way for the complex, literate world we inhabit today. Understanding how and why writing began in Mesopotamia isn’t just a historical curiosity; it’s a journey into the very foundations of human civilisation and communication.

To truly appreciate this leap, we need to travel back in time to the fourth millennium BCE. Mesopotamia was a crucible of innovation. Driven by the fertile lands flanking the rivers, agriculture flourished, allowing populations to grow and settle in one place. These settlements evolved into the world’s first true cities, places like Uruk, Ur, and Nippur. With cities came complexity: burgeoning trade networks, centralised religious practices centred around large temples, organised labour for massive irrigation projects, and the beginnings of state administration. Kings and priests needed ways to manage resources – grain, livestock, textiles, labour – on an unprecedented scale. Human memory, fallible and limited, was simply no longer sufficient to keep track of the intricate economic and administrative details of these early urban centres. As the archaeologist Denise Schmandt-Besserat argued compellingly, the initial impetus for writing appears to have been overwhelmingly economic: the mundane but vital need for reliable accounting [1]. Before script emerged, Mesopotamians used a system of small clay tokens of various shapes, representing different commodities like jars of oil, measures of grain, or heads of livestock. These tokens could be sealed within clay balls, called bullae, serving as tamper-proof bills of lading accompanying goods.

The leap towards actual writing seems to have occurred when administrators realised they could simply impress the tokens onto the outside of the bulla before sealing them inside, creating a visible record of the contents. Soon, the tokens themselves became redundant; simply impressing the shapes, or drawing pictures representing the tokens (pictograms), onto a flattened piece of clay was enough. This happened around 3500-3200 BCE in cities like Uruk. These early clay tablets, bearing simple pictures and numerical impressions, represent the earliest recognisable form of writing. Initially, these pictograms were quite literal – a drawing of a head to mean ‘head’, a stalk of barley for ‘barley’. They were primarily used for administrative lists: goods received, rations distributed, taxes levied. This proto-writing was functional but limited; it couldn’t easily represent abstract concepts, names, or complex sentences. A major transformation was needed for it to become the flexible tool we recognise writing as today.

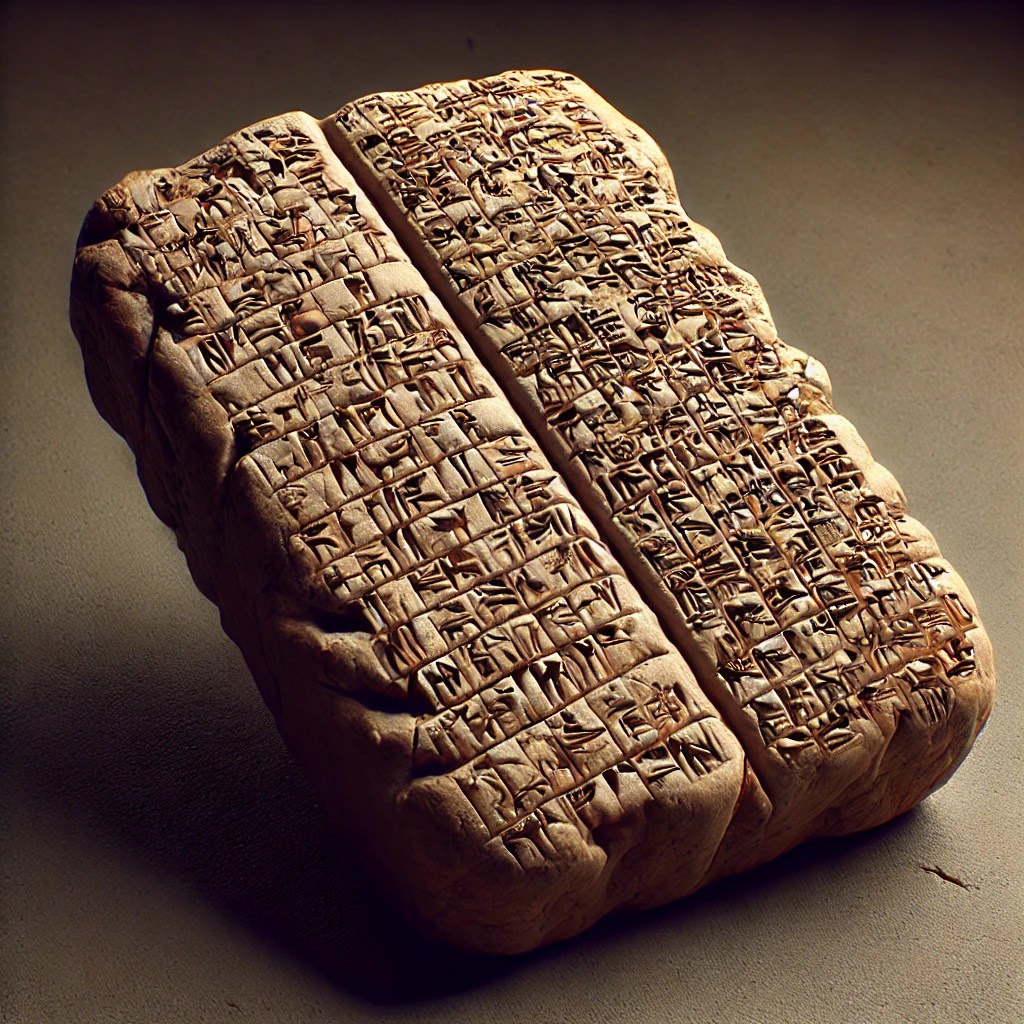

This transformation led to the development of cuneiform, a name derived from the Latin ‘cuneus’, meaning ‘wedge’, which perfectly describes the script’s appearance. Around 3100 BCE, scribes began using a reed stylus, cut to have a triangular or wedge-shaped tip, to press marks into wet clay tablets rather than drawing lines. This was faster and produced cleaner, more standardised symbols. Pressing the stylus at different angles created distinct wedge patterns. Over time, the original pictograms became increasingly abstract and stylised, evolving into combinations of these wedge marks. Crucially, the script underwent a process called rebus principle, where symbols began to represent sounds rather than just objects or ideas (logograms). For example, the Sumerian word for ‘arrow’ was ‘ti’. Since the word for ‘life’ also sounded like ‘ti’, the symbol for ‘arrow’ could be used to represent the abstract concept of ‘life’. This shift towards representing sounds (phonetisation), specifically syllables (syllabograms), was revolutionary. It allowed scribes to write down names, grammatical elements, and abstract ideas, making it possible to record the Sumerian language much more completely. As Dr Irving Finkel, a specialist in cuneiform at the British Museum, notes, “Cuneiform writing, on durable clay, was used for some 3,000 years to write perhaps fifteen different languages… a graphic triumph of the first order” [2]. This adaptability was key to its longevity and spread.

The tools of the cuneiform scribe were simple yet effective: locally abundant clay and reeds from the riverbanks. Scribes would knead the clay into a tablet shape, often palm-sized for everyday records but sometimes much larger for literary or royal texts, holding it in one hand while impressing the wedges with the stylus held in the other. The direction of writing eventually standardised, moving from vertical columns read top-to-bottom and right-to-left, to horizontal lines read left-to-right. Once inscribed, tablets could be left to dry in the sun, making them reasonably durable for short-term records. For important documents intended to last – royal decrees, religious texts, legal codes, literary works – the tablets were often baked in kilns, making them virtually indestructible, which is why archaeologists have been able to recover hundreds of thousands of them. These tablets provide an unparalleled window into Mesopotamian life.

The applications of this new technology rapidly expanded far beyond simple bookkeeping. Writing became indispensable to the state. Rulers used it to issue laws, such as the famous Code of Hammurabi from Babylon (c. 1754 BCE), inscribed on a towering stone stele for public view, establishing legal precedents and reinforcing royal authority [3]. Administrators used it for detailed census data, land surveys, and managing complex irrigation systems. Diplomats exchanged letters written on clay tablets, often sent via messengers across vast distances; the Amarna letters, a cache found in Egypt, reveal intricate diplomatic correspondences between the Egyptian pharaohs and rulers in Mesopotamia and the Levant during the 14th century BCE [4]. Religion also embraced writing. Scribes recorded hymns, prayers, rituals, omen collections, and foundational myths like the Epic of Gilgamesh, which explored themes of kingship, mortality, and the human condition, preserving their cultural and spiritual heritage [5]. Knowledge itself became a domain codified by writing. Mesopotamians developed sophisticated systems of mathematics (including the sexagesimal, base-60, system from which we derive our 60-minute hour and 360-degree circle), compiled astronomical observations used for divination and calendrical purposes, and recorded medical knowledge, listing diagnoses and prescriptions [6].

Education became formalised around the acquisition of literacy. Scribal schools, known in Sumerian as ‘edubba’ (‘tablet house’), emerged, primarily educating the sons of the elite. Learning cuneiform was arduous. Students spent years copying signs, memorising vocabulary lists (lexical texts), practising mathematics, and studying classic literature. Discipline could be harsh, but graduating as a scribe offered a prestigious career path in the temple, palace, or private enterprise. As the Assyriologist Jean Bottéro put it, writing created “a gulf… between those who could read and write and those who could not,” establishing a knowledgeable elite [7]. These scribes were not just copyists; they were the intellectuals, administrators, and custodians of knowledge in their society.

The success and flexibility of cuneiform led to its adoption and adaptation by numerous neighbouring cultures who spoke different languages. Akkadian, a Semitic language spoken by the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians who came to dominate Mesopotamia after the Sumerians, became the primary language written in cuneiform for centuries, serving as a lingua franca across the Near East. But the script was also adapted to write Eblaite, Elamite, Hittite (an Indo-European language), Hurrian, and Urartian, among others. Even Old Persian, while eventually developing its own simplified cuneiform-inspired syllabary, initially used Mesopotamian cuneiform traditions. This widespread use underscores the profound impact of the Mesopotamian invention beyond its geographical origins. The decipherment of cuneiform in the 19th century, largely thanks to the work of scholars like Henry Creswicke Rawlinson who painstakingly copied and translated the multilingual Behistun Inscription in Iran, unlocked these ancient civilisations and their rich histories for the modern world [8].

The invention of writing in Mesopotamia was, without doubt, a watershed moment in human history. It transformed societies from primarily oral cultures to literate ones, enabling levels of administrative complexity, cultural transmission, and knowledge accumulation previously unimaginable. It allowed for codified laws, intricate economic planning, long-distance diplomacy, and the preservation of literature and scientific thought that would influence subsequent civilisations. While cuneiform itself eventually died out, replaced by simpler alphabetic scripts like Aramaic by the early centuries CE, its fundamental contribution was monumental. It demonstrated the very possibility of representing spoken language in a durable, physical form. This Mesopotamian system, born from the practical need to count sheep and barley, laid the conceptual groundwork for all subsequent writing systems, including the alphabet you are reading now. It separated the knower from the known, allowing ideas to exist and travel independently of the person who conceived them. It gave humanity a shared, external memory.

Reflecting on this legacy, we see how writing facilitates complex thought, critical analysis, and the building of knowledge across generations. The Mesopotamians, through their wedge-shaped marks on clay, did more than just invent a script; they fundamentally altered the human capacity for organisation, reflection, and collective learning. Although separated from us by millennia, their innovations remain deeply embedded in the fabric of our literate world. One might pause and wonder: without those ancient scribes painstakingly pressing reeds into clay, how might the story of human civilisation have unfolded differently?

References and Further Reading:

1. Schmandt-Besserat, Denise. How Writing Came About. University of Texas Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0292777040.

2. Finkel, Irving L., and Taylor, Jonathan. Cuneiform. British Museum Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0714111889. (Quote adapted for context, concept widely attributed to Finkel’s work).

3. Roth, Martha T. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. SBL Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0788503788. (Provides context and translation of Hammurabi’s Code).

4. Moran, William L. The Amarna Letters. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0801842511.

5. George, Andrew R. The Epic of Gilgamesh: A New Translation. Penguin Classics, 2000. ISBN 978-0140447217.

6. Robson, Eleanor. Mathematics in Ancient Iraq: A Social History. Princeton University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0691091822.

7. Bottéro, Jean. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods. Translated by Zainab Bahrani and Marc Van De Mieroop. University of Chicago Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0226067278. (Concept regarding the societal impact of literacy).

8. Adkins, Lesley. Empires of the Plain: Henry Rawlinson and the Lost Languages of Babylon. Thomas Dunne Books, 2003. ISBN 978-0312330026.

9. Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000-323 BC. 3rd Edition. Wiley-Blackwell, 2015. ISBN 978-1118718179. (General overview of the period and significance of writing).

10. Walker, C. B. F. Cuneiform (Reading the Past). British Museum Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0714180595. (Concise introduction to the script).

Leave a comment